Mark Parascandola is a documentary fine-art photographer based in Washington DC. His work explores how photography, and the movies, shape our perceptions of history and create ambiguity between reality and make-believe. A PhD epidemiologist by training, he draws on methods of historical and public health research in investigating subjects and locations. His work has been exhibited widely in the US, Spain and China. Mark was awarded Individual Artist Fellowships from the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities 2014 and 2018 and was a Finalist for the Sondheim Prize 2011 and for Critical Mass 2012, 2016, and 2019. His photobook Once Upon a Time in Almería: The Legacy of Hollywood in Spain was published by Daylight Books in 2017. The work from that project was the subject of a solo exhibition at the Embassy of Spain in Washington DC and has since traveled to numerous locations. His latest photobook Once Upon a Time in Shanghai (Daylight, November 2019) documents the rapidly-expanding movie industry in China. The book was awarded First Place in the Documentary Book Project category in the 2019 International Photography Awards and related work was selected for the “Best of Show” exhibition at the Lucie Awards in New York City October 2019.

Books

- ‘Once Upon a Time in Shanghai: Behind the Scenes of the Chinese Film Industry’, (Daylight Books, 2019)

- ‘Once Upon a Time in Almería: The Legacy of Hollywood in Spain’, (Daylight Books, 2017)

- ‘Carabanchel’, (Self-published, 2014) – photographs and text documenting the abandoned Franco-era prison in Madrid

Awards

- First Place, Documentary Book Project, 2019 International Photography Awards

- Artist Fellowship, DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities, 2014, 2018

- Finalist, Critical Mass 2012, 2016, 2019

- Semi-Finalist, Janet and Walter Sondheim Artscape Prize, 2013

- Semi-Finalist, Trawick Prize, 2013

- Finalist, Janet & Walter Sondheim Artscape Prize 2011

- Distinguished Artist prize, Enclave Arts Competition

Selected Exhibitions

2019- “Best of Show” Exhibition, The Lucie Foundation, New York City (traveling)

- Once Upon a Time in Shanghai, Naiman International Photo Festival, Inner Mongolia, China

- China Film (solo exhibit), American Society of Interior Designers, Washington DC

- The Dog and Pony Show: A Sondheim Finalist Alumni Exhibition, Area 405, Baltimore, MD

- Photography by Mid-City Artists, Art14 at Coldwell Banker, Washington DC

- FY18 Visual Arts Fellowship Program Applicants Exhibition, DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities, Washington DC

- Once Upon a Time in Almería (solo exhibit), Escuela de Arte, Almeria, Spain

- Mirror to the World, Photoworks at Glen Echo, Maryland

- Typecast, Hillyer Art Space, Washington DC

- China Film (solo exhibit), BlackRock Center for the Arts, Gaithersburg, Maryland

- Once Upon a Time in Almería (solo exhibit), Instituto de Estudios Almerienses, Almeria, Spain

- Photobook 2014, Griffin Museum of Photography, Winchester, MA

- La Chanca: Living on the Margin (solo exhibit), Studio 1469, Washington DC

- Art Night 2014, Hickok Cole Architects and WPA, Washington DC

- Carabanchel (photobook release), Studio 1469, Washington DC

- Once Upon a Time in Almería (solo exhibit), Miami Dade Public Library, Miami FL

- Sondheim Artscape Prize 2013 Semi-Finalist Exhibition, Maryland Institute College of Art, Baltimore, MD

- Options 2013 (Washington Project for the Arts), Arlington Arts Center, Arlington VA

- Photo/Video 2013, Artisphere, Arlington, VA

- Once Upon a Time in Almería (solo show), Embassy of Spain, Washington DC

- Emerging Artist Showcase (solo show), ArtSee and TTR Sotheby's International Realty, Washington DC

- Photo 2011: Annual Juried Mid-Atlantic Photo Exhibition, Terrace Gallery at Artisphere, Arlington, VA

- Sondheim Artscape Prize: 2011 Finalists, Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MD

- Like Nowhere I've Been: Landscapes de un Sueño, Evolve Urban Arts Project, Washington DC

- Flash, FotoDC, Crystal City, VA

- Mirror to the World, Photoworks, Glen Echo, Maryland

- Cult: 10/29 Group Photography Exhibition, The Gallery at Social, Washington DC

- Thoreau's Legacy, Union of Concerned Scientists, Washington DC

- Friend Request: MCA Invitational, Art 17 at Coldwell Banker, Washington DC

- Social Network in the Neighborhood, DC Loft Gallery, Washington DC

- Spanish Ghosts: Spain's Abandoned Architecture (solo show), Studio B at Biagio Fine Chocolate

- Idylls, organized by the Washington Project for the Arts and the World Bank Art Program, Washington DC

- This District Moment: Report from the Streets, Pyramid Atlantic Arts Center, Silver Spring MD

- Temporary Constructions: New Photographs by Stirling Elmendorf and Mark Parascandola, Nevin Kelly Gallery, Washington DC

- Earth in the Balance, Union of Concerned Scientists, Washington DC

- Images of Washington, DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities, Washington DC

- Face of the World, VisArts – Metropolitan Center for the Visual Arts, Rockville, MD

- 40X26.667: A Photographic Collaboration by Stirling Elmendorf and Mark Parascandola, Caramel, Washington DC

- Double Vision: The Photographic Work of Yanina Manolova and Mark Parascandola, Nevin Kelly Gallery, Washington DC

- 6th Annual International Photography Competition, Fraser Gallery, Bethesda, MD

I am a documentary fine-art photographer based in Washington DC and Almeria, Spain. My work is informed by my training and background in history and public health research. I focus on creating series of images around a location or group of locations that tell a story. I am especially interested in how photographs and movies can shape our perceptions of history and truth or create ambiguity between reality and make-believe. The final product is in the form of a series of large scale prints for exhibition or a photobook monograph with text.

As a historian and public health researcher, I pursue my photographic projects with an obsession for detail and thorough exploration of the theme. Even before visiting a location to take photographs, I conduct extensive research to understand the history of a place and how it has been represented in popular media, talking with experts or locals and seeking out books or documents about the locations and their history. I was trained in both history and epidemiology—the science of understanding causes of disease at the population level. Thus, rather than pursuing the stories of individuals, my photographic projects focus on expansive narratives about a community or an industry—the 80-year history of a notorious prison for political prisoners, the legacy in the landscape from two decades of Hollywood filmmaking in the south of Spain, and the super-sized movie industry in China.

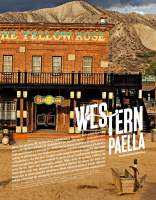

As a photographer, I am intrigued by how photographs and films can be used both as documentary evidence and to create imaginary worlds. There is often a tension between truth and fiction in film and photography. Photographic images can give us a vivid sense of reality yet may reveal only part of a story, remaining ambiguous or even misrepresenting reality. My recent work has focused on the architecture and landscapes of the movies. As a photographer, I appreciate how filmmakers and cinematographers create realities out of a mix of real and constructed elements. Moreover, movies can shape our ideas about historical truth. For example, as Italian films made in Spain shaped Americans’ perceptions of the American West. The Western film sets left behind 50 years ago in the desert of southern Spain, and still there today, suggest a ghost town in the southwest of the United States. Yet they are fake, constructed solely for a fictional story, imposters for real history.

I have been inspired by the photographic work of filmmakers who have worked in some of the same locations, seeking wide-open spaces, exotic landscapes, and dramatic lighting. I strive for vivid colors and rich textures in my work. Although the images document specific places, my aim is more to reference them as viewers may have seen them on the movie screen rather than to represent them in an objective or journalistic way. The images are often set in a desolate landscape among empty buildings, invoking a sense of emptiness and nostalgia for something lost.

I am influenced by other artists who have a fascination with, as well as an ambivalence towards, human impact on the landscape. Film directors like Sergio Leone, who worked in the south of Spain, created dramatic compositions focused on one or two gunmen in front of a vast desert landscape. Photographer Richard Misrach reveals the damage done to natural spaces from atomic weapons tests or industrial pollution, using powerful yet beautiful images accompanied with well-researched text. I have also been influenced by painters like Giorgio De Chirico and Edward Hopper who create landscapes and places that contain familiar elements but appear distant and foreign.

My work involves long term projects, pursued over years with multiple visits to key locations under different lighting and weather conditions, or times when few people are around. I shoot in digital format as it gives me control over the entire process from capturing the photo to the final print. My primary camera is a Canon 5D Mark III camera, along with two or three key lenses, including a tilt-shift lens for architecture. Editing the resulting images and creating prints is also an important and consuming part of the process. While I do not substantially alter the elements in the image, the colors and lighting are chosen and adjusted to give a particular mood or atmosphere. The final product is the printed work, and I do my own printing using a Canon printer with archival inks and Hahnemuhle photo rag paper. Holding the physical print in my hands and being able to examine it is a key aspect of appreciating the work. The viewer can see and feel the texture and detail on the paper and the rich colors that cannot be reproduced on a computer screen. For exhibition, I create large scale prints, from 3 to 6 feet wide, sometimes using a panoramic format to invoke the aspect ratio of the movie screen.

Photography provides a window onto the world. Rather than simply serving as record of what can be seen, it often requires us to piece together a larger story from incomplete information. Photography is forced to rely on what is visible, but can serve as a tool to explore that which is hidden. In this sense, it shares much in common with science or history. My work has often focused on visual elements that are partial evidence of a larger story, such as film sets or architectural remains. Thus, I continue to be inspired by photography as a tool for communicating and for understanding our world.

Articles

-

Bloomberg, October 29, 2019

Behind the Scenes of China’s Multibillion-Dollar Film Studios -

Wired, November 11, 2019

China's Sprawling Movie Sets Put Hollywood to Shame -

New York Times, November 20, 2019

These Books Take You to a Wild Place -

SupChina, November 20, 2019

‘The Ambiguity Between Truth And Fiction’ Interview -

Radii China, November 24, 2019

Photographing Behind the Scenes of the Chinese Film Industry -

It's Nice That, November 29, 2019

The mega Chinese film studios that put Hollywood to shame -

Daily mail, November 29, 2019

Mark Parascandola documents the scenery and sets of China’s booming film industry -

DailyMail.com, June 1, 2017

The Spanish Spaghetti Western ghost town where abandoned Hollywood film sets are still standing in the desert almost 50 years on -

La Voz de Almeria, October 10, 2015

Fotografía y cine de Almería a través de Mark Parascandola -

La Voz de Almeria, October 10, 2015

Paseo fotográfico por los vestigios del cine de Almería -

La Voz de Almeria, October 9, 2015

Mark Parascandola expone sus fotografías en el Almería Western Film Festival -

Versovia.com, October 8, 2015

Mark Parascandola expone en Tabernas su mirada por escenarios olvidados del cine en Almería -

Washington Post, December 13, 2015

Parascandola and Smallwood -

Washington Post Weekend, October 10, 2014

Gallery Opening of the Week -

DeborahKalbBooks.blogspot.com, October 17, 2014

Q&A with Mark Parascandola -

DCist, July 8, 2014

Photographer Mark Parascandola (interview) -

Costa Almeria News, May 9-16, 2013

Almeria's past on display -

Washington Diplomat, October 31, 2012

'Once Upon a Time,' Almería was home to cowboys and Cleopatra -

Washington Post, November 8, 2012

'Signals' shows there's plenty going on in Washington's art scene -

WAMU Metro Connection, October 26, 2012

Photographer captures ghostly "Hollywood of Europe' on film (radio) -

La Voz de Almería, November 28, 2011

Mark Parascandola, la fotografía de lo que queda tras el ser humano -

Washington Post, July 29, 2011

Five artists lead us down varied streets -

PinkLineProject.com, July 10, 2011

Almerian Narratives through Abandoned Architecture (interview) -

Urbanite, July 5, 2011

Visual Arts Cliffhanger -

Baltimore Sun, June 25, 2011

Sondheim Prize finalists engage senses, issues -

Art-full Life (blog of BMA Director Doreen Bolger), July 1, 2011

Sondheim Artscape Prize Exhibition: Abandoned Places -

Washington Post, March 11, 2011

Photographers Share Tips for Budding Shutterbugs -

Montgomery Gazette, March 25, 2011

Glen Echo gallery holds up 'mirror' -

La Voz de Almeria, March 15, 2011

Mark Parascandola exhibe en Washington sus fotos sobre Almeria -

Borderstan, January 4, 2011

Mark Parascandola: Abandoned Architecture -

Washington City Paper, November 3, 2010

Cult: 10/29 (review), City Lights picks -

Yeahbaby (bmibaby in flight magazine), October-December 2010

The Insider: Almeria, Spain (interview) -

La Voz de Almeria, December 13, 2009

Mark Parascandola: Entrevista (interview) -

FotoweekDC.org

The Top 10 Must Attend Fotoweek Exhibits -

The Dupont Current, November 12, 2008

Photoweek show spotlights architectural changes