Fifty Years Ago: Aqaba in Almeria

Fifty years ago, in April of 1962, the Algarrobico beach on the southeastern coast of spain was bustling with activity as two hundred local workers constructed a replica of the Red Sea port of Aqaba circa 1916 for the filming of Lawrence of Arabia. They took three months to construct 300 false-front buildings and a quarter mile sea wall. The crew planted palm trees, trucked in from Alicante, placed four full-size canons on the hills above, and brought 450 horses and 150 camels from Morocco. Hundreds of local fishermen and gypsies served as extras.

In the film, British officer T.E. Lawrence and his Arab followers make the arduous trek across the Nefud desert to mount a surprise attack from inland; the city’s defenses are all directed out towards the sea. From a ridge overlooking the port, the camera pans to the right, following the stampede of warriors on camels and horses into the city before resting on an impotent cannon pointed at the water. It is one of Director David Lean’s most memorable scenes.

Lean had intended to shoot the entire film in Jordan, on the same terrain where Lawrence had waged his campaign. But by the end of September 1961, Lean and crew had been shooting under harsh conditions in the deserts of Jordan for 117 days, were behind schedule and over budget, and had only 45 minutes of footage. The costs (both financial and psychological) of working 200 miles into the desert were high. Producer Sam Spiegel was worried that Lean had become obsessed with the desert, and he was increasingly nervous about growing political debate in Jordan over the film. Someone at Columbia Pictures reported that there were deserts in the south of Spain. Independent American producer Samuel Bronston had recently made El Cid and King of Kings in Almeria. So Spiegel shut down the production and informed the crew they would be moving to Spain. Lean felt betrayed. He wrote Spiegel from the desert: “you won’t touch this place for backgrounds, for after all they are the real backgrounds. … You can’t beat Aqaba for Aqaba.

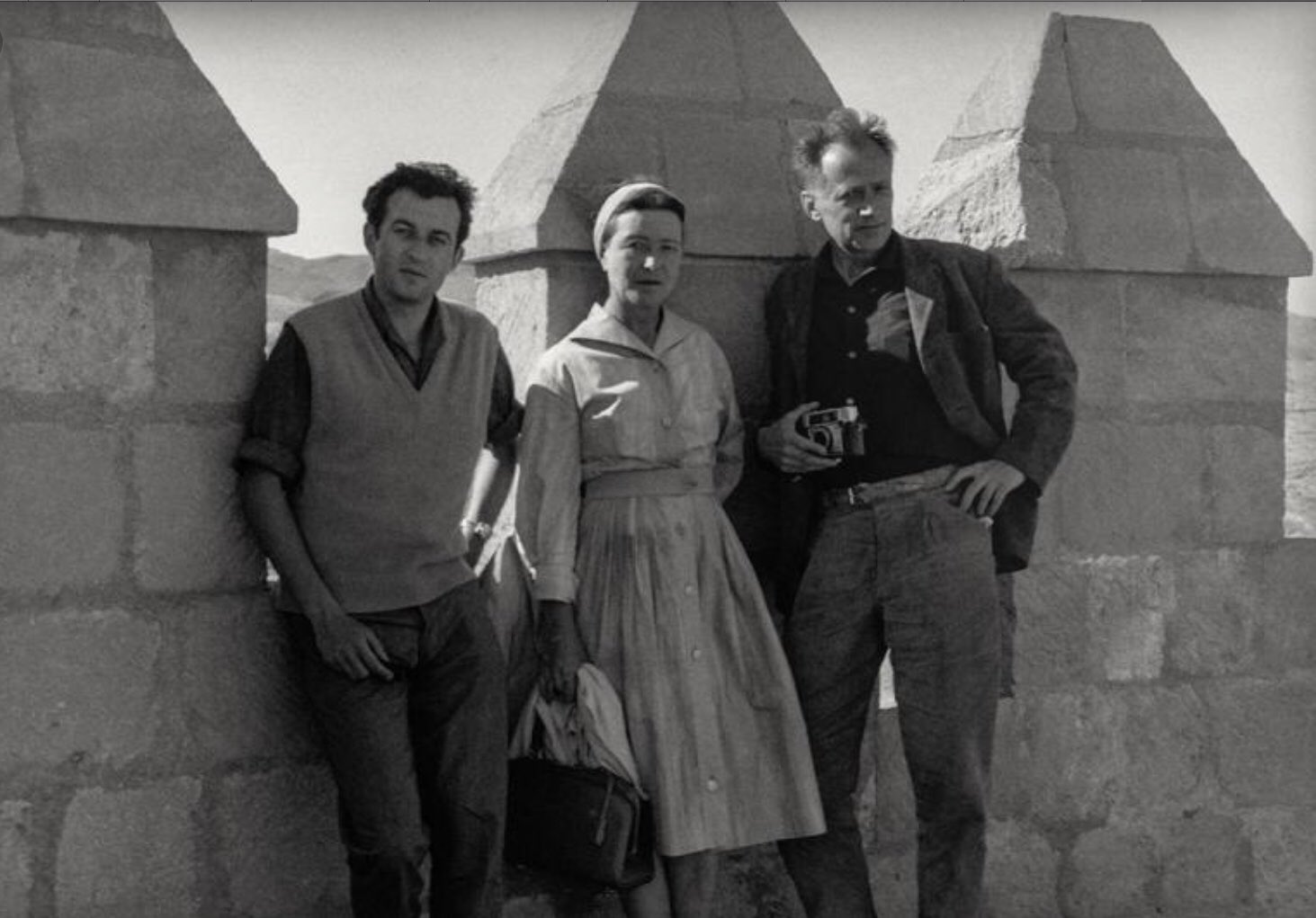

Andre de Toth, one of Lean’s second unit directors, was sent ahead to scout for locations. Sixty years old, he was a flamboyant character with an eye patch that gave him the appearance of a pirate. He was also a pilot. “I flew my own plane and went all over the place. Then I found Almeria, he recalled. Almeria was barren, dry and rugged, but it lacked the monumental desert vistas of Jordan. Lean planned for closer camera angles to suit the dramatic intensity and action of the second half of the film, which would also serve to make the shift in locations less noticeable. But they still had one expansive scene left–the attack on Aqaba. Production designer John Box found the ideal location to construct the sprawling set. Outside the small fishing village of Carboneras was a dry river bed running between barren hills and ending at the beach. The rocky coastline beyond stretched out into the sea. When it came time for filming, the attack was done in one take with multiple cameras (among the cameramen was a young Nicolas Roeg). In the end, the scene was far more dramatic than the real city of Aqaba, considerably modernized by the 1960s, could have been.

In the final film, the first view of the landscape of Almeria, and the departure from Jordan, comes when Lawrence and Sheik Ali peer down at the city of Aqaba the night before the attack. The scene cuts abruptly from the wide-open golden desert, enormous twisted rock formations jutting out of the sand, to oscillating peaks and gulches of the spanish coast silhouetted at night. The rest of Lawrence was made in Spain and Morocco. Sand dunes along the coast of Almeria became the setting for the explosion and attack on the railway. A dry riverbed in Tabernas was planted with palm trees to create the desert oasis that Lawrence’s army stops at on the way to Aqaba. A casino in Seville, originally built for the Iberian-American Exhibition of 1929, became the Damascus Town Hall. And the city streets of Seville and Almeria stood in for Cairo. After the filming was over, the entire Aqaba set was dismantled and the construction materials given to local farmers. Today the old riverbed has a highway running over it, and alongside the beach lies a massive uncompleted luxury hotel, seen in the image above. Watching the film again, one can easily recognize the distinctive chiseled rocks extending out into the water.